On July 12, 1979, the pop-music genre Disco was “killed” by an organized public backlash with the infamous “Disco Demolition” night at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. The catastrophic incident, which led to at least nine injuries, 39 arrests and the cancellation and forfeit of the game to the Detroit Tigers, is widely seen by many as dealing disco its eventual, sustained death blow. Undaunted, the annoying form, based on 120 beats per minute, simply changed its clothes and hairstyle and slyly set up shop in the 80s.

Disco as a musical style emerged in the mid-1960s to early 1970s from America’s East Coast urban nightlife scene, where it originated in house parties and makeshift discothèques, and reached its peak popularity between the mid-70s and early 80s. Disco’s initial audiences in the U.S. were club-goers from the African American, Italian American, Latino, gay, and psychedelic communities in Philadelphia and New York City beginning in the late 1960s.

Disco may be seen as a reaction to both the domination of rock music and the stigmatization of dance music by the counterculture during this period; several dance styles were also developed during this time, including the Bump, Hustle, Funky Chicken, Disco Finger, Robot, Lawnmower, and YMCA Dance. Disco dance contests proliferated at local clubs, school dances, and family functions; your humble scribe came in second to “Lenny” Leonard Barnes at the Levy Bot Mitzvah in the Fairlane Hyatt, circa 1978.

The disco sound often had several components, a “four-on-the-floor” beat, an eighth note or 16th note open hi-hat pattern on the off-beat, and a prominent, syncopated electric bass line. In most disco tracks, string and horn sections, electric piano, and electric rhythm guitars created a lush background sound. Orchestral instruments such as the flute were often used for solo melodies, and lead guitar was far less frequently present in disco than in rock. Most numbers had an ample portion of synthesizer poured overall, particularly those of the late 1970s.

Discothèque-goers often wore glamorous, expensive and extravagant fashions for nights out at their local disco club. Some women would wear sheer, flowing dresses, such as Halston’s offerings, or loose, flared pants. Other’s wore tight, revealing, sexy clothes, such as backless halter tops, “hot pants” or body-hugging spandex. Men would wear shiny polyester Qiana shirts with colorful patterns and pointy, extra wide collars, preferably open at the chest. Men often wore Pierre Cardin suits, three piece suits and, double-knit polyester shirt jackets with matching trousers known as the leisure suit.

Well-known disco performers included Donna Summer, the Bee Gees, Gloria Gaynor, KC and the Sunshine Band, the Village People, Thelma Houston, and Chic. While performers and singers garnered much public attention, record producers working behind the scenes played an important role in developing the “disco sound.” Many non-disco artists recorded disco songs at the height of disco’s popularity, and films such as Saturday Night Fever (1977) and Thank God It’s Friday (1978) contributed to disco’s rise in mainstream popularity

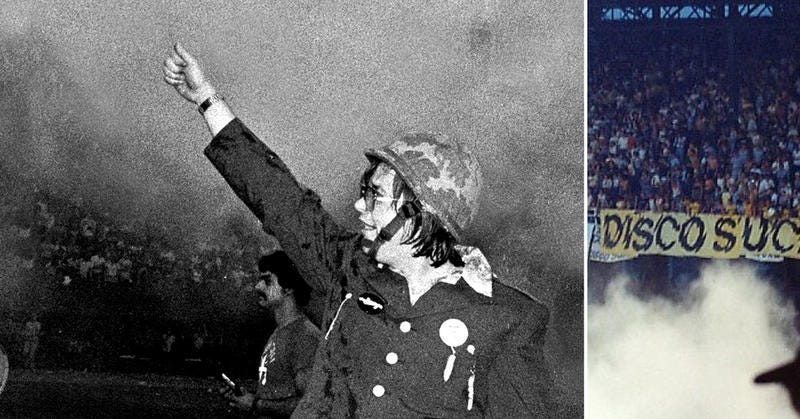

Disco sparked a strong backlash from rock music fans. This opposition was prominent enough that the White Sox, seeking to fill seats at Comiskey Park during a lackluster season, engaged Chicago shock jock and anti-disco campaigner Steve Dahl for the promotion at the July 12 doubleheader. Dahl’s sponsoring radio station was 97.9 WLUP, so attendees would pay 98 cents and bring a disco record; between games, Dahl would destroy the collected vinyl in an explosion.

White Sox officials had hoped for a crowd of 20,000 or so, 5,000 more than usual. Instead, at least 50,000 fired-up, disco-hating Chicagonians, including tens of thousands of Dahl’s angry adherents, packed the stadium, and thousands more continued to sneak in after gates were closed. Countless records were not collected by staff and flew dangerously from the stands like flying discs; general mayhem continued to build after Dahl blew up the collected records.

Swiftly escalating into a full-blown riot, up to 7,000 crazed fans flooded the field amid blasting baby-fireworks, destroyed the batting cages, ripped up all four plates, savaged the turf and lit a bonfire in centerfield. Looking on in horror, venerable announcer Harry Caray and owner Bill Veeck pleaded with the melee to no avail. Detroit skipper Sparky Anderson refused to field his team on the smoking surface and the party eventually broke up.

The second game was initially postponed, but forfeited by the White Sox to the Detroit Tigers the next day by order of American League president Lee MacPhail. Disco Demolition Night preceded, and may have helped precipitate, the perceived decline of disco in late 1979.

Some scholars and disco artists have described the event as expressive of racism, homophobia and toxic political division. Disco Demolition Night remains well known as one of the most extreme promotions in sports and music history, and yet, the genre that would not die nimbly lives on the pop charts to this day. And the often racist, homophobic, and ignorant impluses of millions men and some women, young and old remain with us as well, minus the mirth.