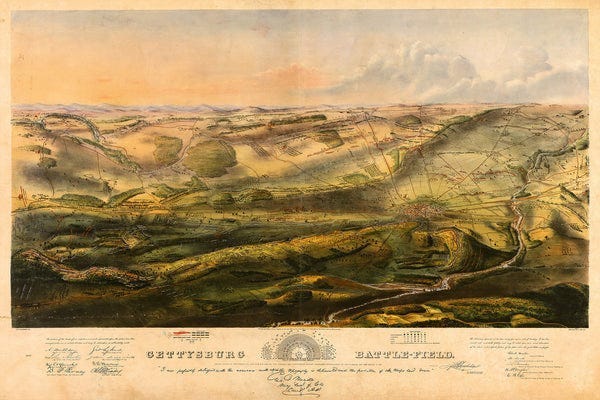

On this very day in 1863, seeking shade from a blazing sun and 87 degree temperatures, the flower of Southern youth waited at the edge of the forest for orders. Determined to wrest a victory from the war’s biggest battle at Gettysburg, C.S.A. Gen. Robert E. Lee, through his obedient Gen. George Pickett, elected to attack the Union center on Cemetery Ridge; they were soundly, savagely repulsed. In what became known as Pickett’s Charge, 12,500 Rebel soldiers stepped off toward glory; a mere handful made it three-quarters of a mile to the Union line, whilst the ground behind them was littered with the wilted and the dead. Witnessing casualties for that maneuver alone nearing 7,000, including 1,123 dead, Lee finally cut losses and the Army of Northern Virginia never set foot in the North again.

Fresh off of his success at Chancellorsville in Virginia in May 1863, Gen. Lee led his army through the Shenandoah Valley to begin his second invasion of the North; the Gettysburg Campaign. With his army in high spirits, Lee intended to shift the focus of the summer campaign from war-torn northern Virginia and hoped to influence Northern politicians to relent on the larger war by penetrating as far as Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, or even Philadelphia.

Elements of the two armies initially collided at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863, as Lee urgently concentrated his forces there, his objective being to engage the Army of the Potomac under the new command of Gen. George Meade, and destroy it. Low ridges to the northwest of town were defended initially by a Union cavalry division under Brig. Gen. John Buford, and soon reinforced with two corps of Union infantry.

However, two large Confederate corps assaulted them from the northwest and north, collapsing the hastily developed Union lines, sending the defenders retreating through the streets of the town to the hills just to the south.

Onthe second day of battle, most of both armies had assembled and taken up positions. The Union line was laid out in a defensive formation resembling a fishhook. In the late afternoon of July 2, Lee launched a heavy assault on the Union left flank, and fierce fighting raged at Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, Devil’s Den, and the Peach Orchard. On the Union right, Confederate probing escalated into full-scale assaults on Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, yet all across the battlefield, despite significant losses, the Union defenders held their lines.

Turning to the Old Northwest, over 2,600 Michigan men fought in the Battle of Gettysburg, and north of 1,111 became casualties. Michigan’s total man (and woman) power for the war was organized into seven infantry and four cavalry regiments, an artillery battery and four companies of sharpshooters.

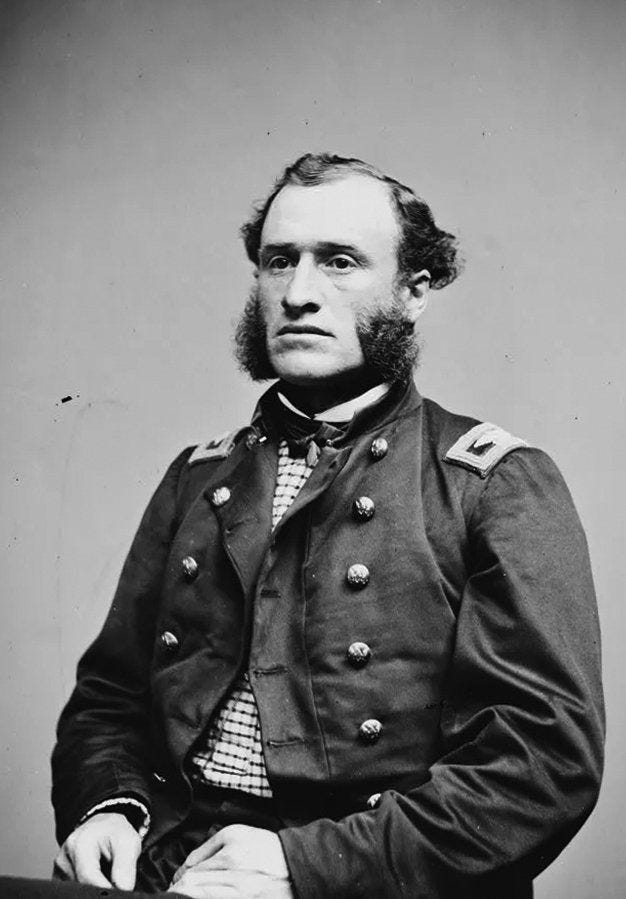

Among these regiments was the famous 24th Michigan Infantry, mustered together at Detroit in the summer of 1862. It joined the existing Iron Brigade, so christened by General George McClellan himself, also featuring units from Wisconsin and Indiana. On the eve of Gettysburg, the 24th was under the command of Colonel Henry Morrow, a veteran of the Mexican War who had served as a Detroit Recorder’s Court Judge before receiving his commission.

Morrow fought bravely and without artillery support on the first day of Gettysburg, was shot in the head, captured, thought to be a goner, set free, and stabilized by the wife of a local judge. On the last day of the battle, Morrow climbed the courthouse steeple and observed Pickett’s Charge with great pity. At nightfall Morrow searched the woods, creek, and fields for surviving wounded from any army, regardless of uniform.

The dead surrounded Morrow, often bloated and blackened beyond recognition, while he culled the wretched remnants from the grim scene. Serving out the war with distinction while wounded twice more, Morrow’s 24th was selected as the honor guard for Lincoln’s funeral and burial at Springfield, Illinois. Morrow abjured a return to the bench after the war and served in the regular Army until his death in 1891.

Demonstrating the same frontier tenacity as their men, several Michigan women found their way to the fray during the Civil War. These included Julia Susan Wheelock Freeman, a spy and missionary who became known as the “Florence Nightingale of Michigan,” Lorinda “Gentle Annie,” Etheridge, a “daughter” of the 2nd Michigan Infantry, and Bridget “Irish Biddy” Deavers. It was in fact Deavers who served under Monroe’s own General George Custer in the 1st Michigan Calvary and was likely present at Gettysburg.

Returning to the action in formerly placid Pennsylvania, with the third day of battle ending disastrously for Lee, he apologized to his men for his perceived failure to prevail, and perhaps, win the war on the eve of Independence Day. However, with casualties numbering nearly a third of Lee’s total force of over 70,000 men and the loss of six generals, the C.S.A. had reached its high-water mark; Grant scored a stunning victory to the west at Vicksburg the same day, Britain rejected further entreaties to assist the South, the Union was further galvanized and the slow, bloody and inexorable Northern victory was now in sight.

Dedicating the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at the battlefield that Fall, Lincoln declared “It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”